I want to start by talking about a particularly illuminating passage in David Graeber and David Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (2021). In it, Graeber and Wengrow (GW) take issue with what evolutionary psychologists such as Robin Dunbar have typically assumed about the nature of human society.

The narrative offered by evolutionary psychologists, GW observes, usually goes something like this: the most basic and tight-knit social unit is the one based on biological kinship. This is presumably evidenced by the structure of ancient and modern hunter-gatherer societies, which supposedly consist of small-scale alliances between pair-bonded, nuclear families with “shared investment in offspring” (279). When larger social structures arose in human history, however, internal group conflicts tended to increase, which necessitated the establishment of centralized institutions and the emergence of sovereign power to maintain social cohesion.

GW’s objection to this type of evolutionary narrative is amusingly simple. Many of us don’t like our families very much. Many, that is, “find the prospect of living their entire lives surrounded by close relatives so unpleasant that they will travel very long distances just to get away from them” (279, 280). Why wouldn’t this also be the case for hunter-gatherers? The idea that hunter-gatherers typically organize themselves in family units, and the related thesis that social ties based on blood relationship are the most enduring, must, therefore, not be simply taken for granted but carefully evaluated.

Anthropological and archaeological data appear to discredit what evolutionary psychologists say about the nature of human group formation. Studies of modern hunter-gatherers, such as the Martu in Australia, have shown that most foragers in residential groups are genetically unrelated (GW cites two studies: Hill et al. [2011] and Bird et al. [2019]). Moreover, a 2017 study of the Agta camps in the Philippines and the BaYaKa camps in the Republic of the Congo suggests that, in hunter-gatherer groups, strong friendships are more important than family ties in predicting shared knowledge and information exchange (much like Facebook and other Internet communities, the authors of the study suggest).

It would be unreasonable to use the behavior of modern hunter-gatherers to infer how humans acted in prehistoric times. Recent genomic evidence has nevertheless suggested that the population structure of modern hunter-gatherer bands can be traced back to at least the early Upper Paleolithic (~32,000 BC), characterized by small group sizes and “limited levels of within-band relatedness.”

GW concludes:

“It would seem, then, that kinship [in forager groups such as the Martu] is really a kind of metaphor for social attachments, in much the same way we’d say ‘all men are brothers’ when trying to express internationalism (even if we can’t stand our actual brother and haven’t spoken to him for years). What’s more, the shared metaphor often extended over very long distances, as we’ve seen with the way that Turtle or Bear clans once existed across North America, or moiety systems across Australia. This made it a relatively simple matter for anyone disenchanted with their immediate biological kin to travel very long distances and still find a welcome” (280).

This passage typifies the general project GW lays out in The Dawn of Everything – to dismantle some of the most popular narratives about the formation of human society. In doing so, GW challenges many deep-seated assumptions we hold about the way in which societies have been and could potentially be organized. If, for instance, it is the case, as GW has argued, that biological kinship does not undergird social attachment, even in small and supposedly primitive hunter-gatherer bands, then an entirely different picture of the nature of human sociality emerges.

GW bases their arguments on the latest research in archaeology and anthropology, which would otherwise have been inaccessible to nonprofessionals. This is made possible by the combination of their respective academic expertise. David Graeber (1961-2020) was an anthropologist and political activist who studied under Marshall Sahlins (1930-2021) at the University of Chicago. David Wengrow is an archaeologist and professor of comparative archaeology at University College London.

Just to illustrate the sheer breadth of GW’s critical project, here is an (incomplete) list of grand narratives about human history that they find in some respect misleading:

- Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651);

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin and Foundation of Inequality Among Mankind (1754);

- Robin Dunbar’s How Many Friends Does One Person Need? Dunbar’s Number and Other Evolutionary Quirks (2010).

- Francis Fukuyama’s The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution (2011);

- Jared Diamond’s The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies? (2012)

- Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (2014)

- Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (2018)

Ultimately, however, GW’s work raises more questions than it gives answers. GW makes innovative points about topics ranging from the advent of agriculture and urban civilization to the historical origins of slavery and private property, but they have, for the most part, refrained from weaving their claims into a coherent grand narrative. The tentativeness of their claims suggests that more research needs to be done in their fields rather than reflecting a lack of intellectual labor or capacity on their part.

Instead of summarizing all of GW’s claims, in what follows, I will focus on what appears to me as two of the important myths about human history that GW’s work succeeds in subverting.

Myth 1: Hobbesian Hawks and Rousseauian Doves

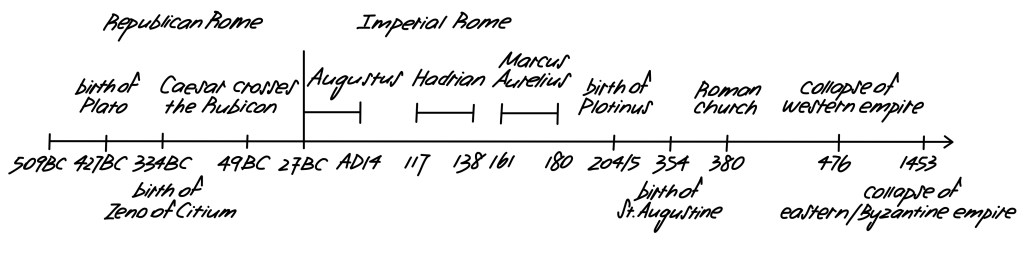

Foundational figures in modern political theory, Hobbes (1588-1679) and Rousseau (1712-1778) both proffered their views on human nature by imagining how humans acted in the original, prehistoric “state of nature,” without the presence of social institutions such as the government, the court, and the police. For Hobbes, the state of nature is basically a state of war (bellum omnium contra omnes), where people fight against each other unless their baser passions are kept in check by a sovereign. Rousseau holds the opposite view. In the Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau accuses Hobbes of having projected into the state of nature values which are in fact products of civil society. Contra Hobbes, he thought that the “savage,” whose action was regulated by the instinct for self-preservation (amour de soi) and feelings of pity (pitié), lived in a prolonged state of childlike innocence and egalitarianism (99).1 For Rousseau, it is the advent of private property, which is in turn brought about by the development of metallurgy and agriculture, that effectively put an end to the peace and egalitarianism of former times:

“The first man who, having enclosed a piece of land, thought of saying ‘This is mine’ and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of civil society. How many crimes, wars, murders; how much misery and horror the human race would have been spared if someone had pulled up the stakes and filled in the ditch and cried out to his fellow men: ‘Beware of listening to this impostor. You are lost if you forget that the fruits of the earth belong to everyone and that the earth itself belongs to no one!’” (109)

Grand narratives about the trajectory of human history are typically modeled after Hobbesian or Rousseauian lines. The former dignifies civil society while the latter condemns it. In the Hobbesian account, progress is dependent upon regulative mechanisms that represses our murderous and selfish instincts. In the Rousseauian account, it is precisely civil society and its laws that irretrievably destroyed the innocent and largely peaceful egalitarianism with which prehistoric humans conducted their lives.

The problem with both of these narratives, GW argues, is that they lead to a pessimistic outlook on the possibilities of human politics. Both presuppose that societies with sizeable populations must be organized rigidly and hierarchically. It matters little that Hobbesians celebrate this whereas Rousseauians laments it: both assume that that’s the direction that human history inevitably takes. For GW, this deterministic view of history is not only unnecessarily pessimistic but also just plainly false, given what we now know about prehistoric human societies.

Current archaeological research now suggests that, in GW’s words,

“From the very beginning, or at least as far as we can trace such things, human beings were self-consciously experimenting with different social possibilities.”

That is, hunter-gatherer bands did not always endorse egalitarian principles (contra Rousseau), neither were ancient cities invariably stratified or organized under a sovereign power (contra Hobbes). In Ukrainian mega-sites (~4000 BC), the Uruk Mesopotamia (~3300 BC), and the Indus Valley (~2600 BC), for instance, the emergence of large urban civilizations did not seem to lead to the concomitant concentration of wealth and power in a sovereign or ruling class.

Myth 2: Societies Developed in Evolutionary Stages

The historical origin of this evolutionary (and materialist) view of social progress can be traced back to an essay written in 1750/51 by French economist Anne Robert Jacques Turgot (1727-1781), entitled “Plan of Two Discourses on Universal History.” In this essay, Turgot outlines what later came to be known as the “four stages” theory of social development. In this view, social progress is measured by the mode of subsistence of its people, which has evolved in four distinct and normally consecutive stages (i.e., hunting, pasturage, farming, and finally commerce). Each stage has associated with it a distinct form of social organization.

What GW has done successfully, I think, is to point to the limitations of theories which view social progress as proceeding in evolutionary stages. For the European thinkers who advocated for this view (e.g., economists like Turgot, Adam Smith, Adam Ferguson, John Miller, etc.), the evolutionary model served to portray European societies as the pinnacle of social progress, while neutralizing what GW has termed the “indigenous critique” of European society which arose among indigenous peoples in the New World. As GW describes it, the American indigenous critique highlighted the perceived inability of European societies to “promote mutual aid and protect personal liberties” and later focused on inequalities of property.

References

Graeber, David, and David Wengrow. The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. Picador / Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. A Discourse on Inequality. Translated by Maurice Cranston, Penguin Books, 1984.

Footnotes