I encountered the American historian John Boswell’s 1980 book, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century, in a San Francisco bookstore specializing in queer literature. It is a work of classical philology and medieval social history that traces the transformation of Western European social attitudes toward gay people between the beginning of the Christian era and the end of the High Middle Ages. It immediately caught my eye because the subject matter appeared relevant to today’s social climate. Many people have strong beliefs about the relationship between religion and sexuality; I was curious to see what a social historian had to say about this topic. I bought the first paperback edition of the book, which I believe is currently out of print, but the 35th Anniversary Edition is on sale here.

In this work, Boswell explores the socio-historical origins of intolerance against gay people in medieval Europe, with a focus on the role played by early Christianity. Was early Christian teaching the cause of prejudice against gay people? Or was Christianity used as rationale for antigay attitudes that in fact arose for other, quite different, reasons?

Boswell’s answers to these questions are as innovative as they are controversial. His main argument is that, in the centuries after the fall of the Roman empire, neither “Christian society nor Christian theology as a whole evinced or supported any particular hostility to homosexuality, but both reflected and in the end retained positions adopted by some governments and theologians which could be used to derogate homosexual acts” (333). If Boswell is correct, then the historical source of Western European intolerance of gay people must be sought elsewhere. Boswell suggests some possible causes in the final chapters of the book, but he gives no definitive answers regarding the ultimate origins of prejudice against homosexuality.

In this post, I would like to provide a chapter-by-chapter summary (not an assessment) of Boswell’s claims and fill in the background needed to understand them. Let us start with classical antiquity.

Chapter 3, “Rome: The Foundation,” where Boswell debunks popular myths about Roman sexuality

Myth 1: Homosexual practices were illegal under Roman law.

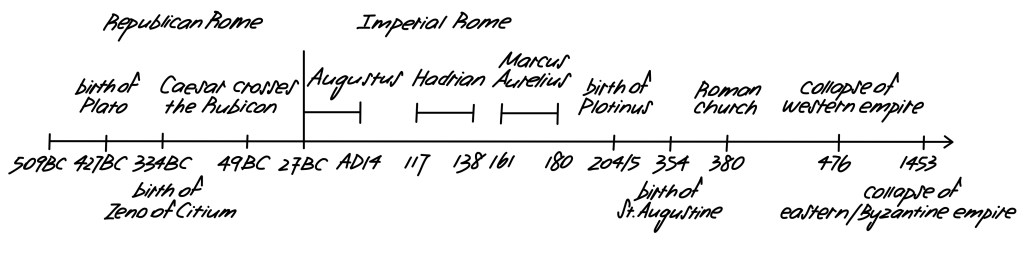

Homosexual practices were legal in republican and early imperial Rome (63-71; fig. 1). Early Roman society almost uniformly assumed that adult males were capable of engaging in sexual relations with both sexes (73). Tolerance of gay people started declining in the fourth century, and homosexual relations were categorically prohibited by Roman law for the first time in the sixth century (127).

Myth 2: Homosexuality and general immorality were associated with, or even caused, the decline of Rome.

The output of gay literature peaked in early imperial Rome rather than during its decline in the third and the fourth century (73). The tolerance of homosexuality thus appeared to have declined along with the empire.

Myth 3: Roman society was characterized by moral anarchy and loveless hedonism.

Roman society enacted a complex set of civil and moral strictures regarding sexuality, even though none were directly related to the regulation of homosexual relations as a specific class (74). The Roman society made strong efforts to protect free-born children from sexual abuse (81). There was social prejudice against adult male citizens who preferred a “passive role” in sexual intercourse (74-77), and against male citizens who became prostitutes (77-80).

Chapter 4, “The Scriptures,” where Boswell discusses the so-called “clobber passages” in Christian Scripture

The “clobber passages” (a term that Boswell himself does not use in the book) are those typically invoked by certain modern interpreters of Scripture to condemn consensual homosexual relations (i.e., Genesis 19:1-38; Leviticus 18:22, 20:13; 1 Corinthians 6:9; 1 Timothy 1:10; Romans 1: 26-27). In this chapter of the book, Boswell argues that, historically speaking, these passages played no demonstrable role in the rise of antigay feelings among Christians.

Chapters 5-6, where Boswell argues that Christian communities were not specifically responsible for social intolerance against gay people in the late Roman Empire

Boswell isolates four type of Christian arguments that came to exert significant influence on the perception of gay people in Europe:

- Animal behavior. The author of the Epistle of Barnabas (c. first century) equated Mosaic prohibitions of eating certain animals with various sexual sins. It was said that the hare grows a new anus every year, the hyena changes its gender every year, and the weasel conceives through its mouth. The Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-250) invoked these zoological examples to argue against homosexuality in his Paedagogus, an instructional manual for Christian parents. The associations between Mosaic law, animal sexuality, and homosexual behavior found their way to the Physiologus, a collection of moralized beast tales and the most popular zoological work in the Middle Ages.

- Unsavory associations. Some Christian writers associated homosexuality with the sexual abuse of minors, accidental incest, and paganism.

- Concepts of “nature.” There is no unitary concept of “nature,” for different schools of thought held different and sometimes incompatible views. Even though there is no sound scriptural basis for the use of “nature” as a moral principle, early Christian thought was influenced by versions of Platonic and Aristotelian concepts of “ideal nature” (e.g., the Platonist Philo posited that any use of sexuality which did not produce legitimate offspring violated “nature”), as well as by Stoic concerns with “natural” morality.

- Gender expectations. Christian church fathers such as John Chrysostom (c. 347-407) objected to homosexuality largely due to its perceived violation of gender norms: “I maintain that not only are you made [by passive intercourse] into a woman, but you also cease to be a man; yet neither are you changed into that nature, nor do you retain the one you had” (In Epistolam ad Romanos, cited in 157).

Boswell nevertheless contends that these theological texts were not determinative of Christian sexual ethics in the late Roman Empire. Boswell lays out several arguments in support of this thesis:

- All organized philosophical traditions grew increasingly intolerant of sexual pleasure under the later Empire, including pagan philosophy (128).

- It appears unlikely that Christians in general subscribed to the extreme asceticism and narrow sexual attitudes of some of their leaders (128).

- The major moral traditions that influenced Christianity would not necessarily have prohibited homosexual relations as an option for Christians (i.e., the Judeo-Platonist schools of Alexandria [163, 164], dualist religious movements such as Manicheaism [128, 129], and Stoicism [129-131]).

- Many writers objected to Christianity precisely due to the supposed sexual looseness of its adherents and even leaders, including engagement in homosexual acts (131-133).

Boswell argues that the decline of Roman tolerance of sexual issues may alternatively be attributed to (1) the increasing ruralization of Roman civilization and ethics, and (2) the growing totalitarianism of Roman government and its control over the lives of Roman citizens.

Chapters 7-11, where Boswell outlines the vicissitudes of popular social attitudes toward gay people in the Middle Ages

In the early Middle Ages, gay people constituted a silent minority. Moral theology of this period treated homosexual practices as at worst comparable to premarital heterosexual intercourse but more often remained silent on this issue (333). In general, Boswell claims, attitudes toward homosexuality grew steadily more tolerant (333).

A gay subculture re-emerged in the eleventh and early twelfth century (1050-1150), along with urban economies and city life. It appeared to have its own slang (e.g., the equivalent of “gay” was “Ganymede”).

Beginning roughly in the late twelfth century, a “virulent hostility” toward homosexuality developed in popular literature as well as theological and legal writings (334). The cause of this shift is unknown and remains to be explored.